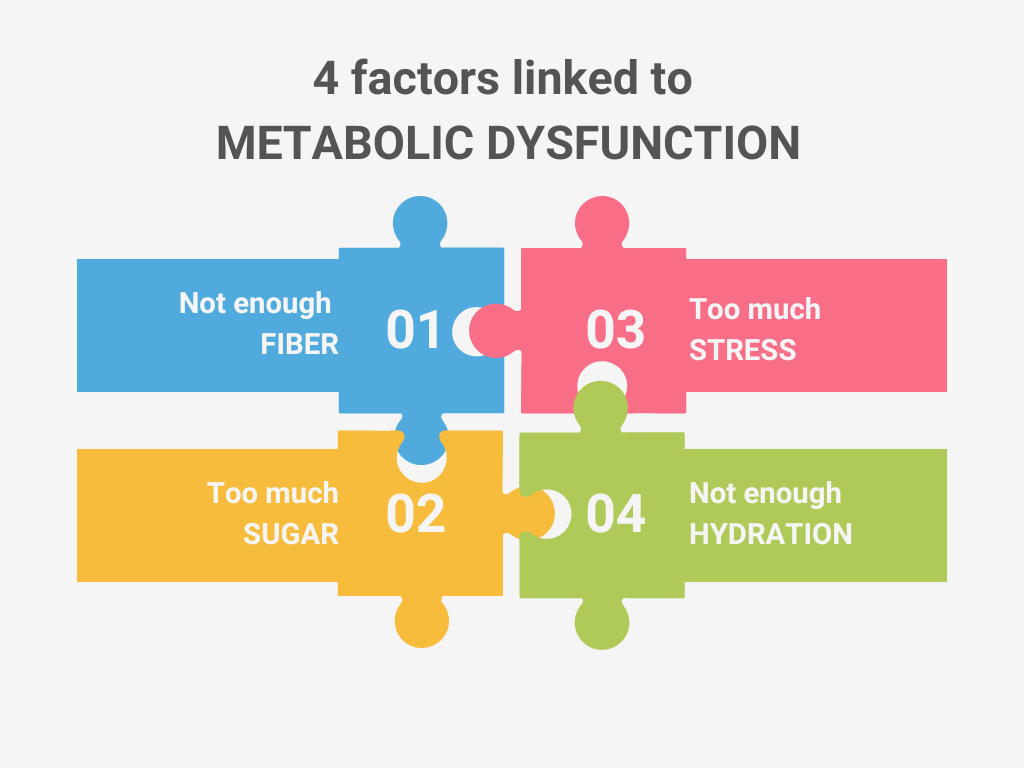

Four Factors linked to Metabolic Dysfunction

When searching for information on improving metabolic function, the solutions are elusive at best and impossible at worst. The information shared online and through social media is often too generic to be helpful—such as “Eat less, move more”—too specific—like “Eat almonds to reduce belly fat”—or even contradictory and potentially damaging. Even books authored by doctors and scientists offer conflicting advice on what actions to take.

It is encouraging that there is a substantial level of attention on the topic of metabolic issues, and scientific and medical research are clearly progressing. However, there does not yet seem to be a clear-cut answer as to why millions of U.S. adults and children are dealing with metabolic syndrome. Hopefully, in time, the causes will become much more clear.

In the meantime, there are common themes in published scientific and medical research that may offer helpful insights. In my reading and research, four factors are most frequently associated with metabolic dysfunction:

1. Not Enough Fiber

Getting enough fiber is associated with reduced metabolic disease risk factors (Quagliani & Felt-Gunderson, 2016). According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020), over 90% of adults do not meet the recommended daily intake of fiber. Nutritional goals vary from 25 to 31 grams a day for adults.

Processed carbohydrates—like crackers and chips—are often stripped of their natural fiber content. Choosing more whole foods, fruits, vegetables, and legumes can help close that gap.

2. Too Much Added Sugar

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 also report that a majority of Americans exceed the recommended limits for added sugar (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020).

We all recognize when we’re indulging in obvious sources of sugar, like cupcakes or donuts. However, added sugars also hide in many foods—such as salad dressing, bread, juice, or pasta sauce. Common types of added sugars are listed on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website.

Fortunately, food labels now make it easier to identify added sugar. Since 2021, manufacturers have been required to include “Added Sugars” on nutrition labels (Magnuson & Chan, 2019). For example, GoGo SqueeZ applesauce lists 13 g total sugars and 0 g added sugars—indicating that no sugar was added during processing.

3. Too Much Stress

Stress has been linked to obesity and metabolic dysfunction (Tomiyama, 2019). The stress may be physiological, psychological, or physical. For anyone struggling with metabolic issues, it’s worth identifying sources of stress that can be reduced or eliminated. Some stressors are obvious, while others may be subtle and chronic.

4. Not Enough Hydration

We’ve all heard the advice to “drink more water,” and research supports it. Inadequate hydration has been associated with higher body mass index (BMI) and obesity (Chang et al., 2016).

The amount of water an individual needs depends on factors such as climate, activity level, and body size. The Mayo Clinic recommends approximately 2.7 liters daily for women and 3.7 liters for men.

References

Chang, T., Ravi, N., Plegue, M. A., Sonneville, K. R., & Davis, M. M. (2016). Inadequate hydration, BMI, and obesity among US adults: NHANES 2009–2012. Annals of Family Medicine, 14(4), 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1951

Magnuson, E. A., & Chan, P. S. (2019). Added sugar labeling. Circulation, 139(23), 2625–2627. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040325

Quagliani, D., & Felt-Gunderson, P. (2016). Closing America’s fiber intake gap: Communication strategies from a food and fiber summit. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 11(1), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827615588079

Tomiyama, A. J. (2019). Stress and obesity. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102936

U.S. Department of Agriculture, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2022, October 12). Water: How much should you drink every day? Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/water/art-20044256

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, January 5). Get the facts: Added sugars. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/php/data-research/added-sugars.html