Solving Metabolic Syndrome Will Take All of Us

Metabolic syndrome, as we know it now, sits at the intersection of modern life—stress, diet, genetics, sleep, sedentary behavior, and the environments we’ve built around ourselves. It manifests in a related cluster of metabolic dysfunctions that include insulin resistance, high blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol, and increased body fat. In the United States, recent analyses of NHANES data from 2017 through March 2020 estimate that about 45.9% of adults meet diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome.

(According to the widely used NCEP ATP III definition, metabolic syndrome is present when three or more of the following five criteria are met:

Waist circumference ≥ 102 cm (men) / ≥ 88 cm (women)

Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL

HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (men) / < 50 mg/dL (women)

Blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg

Fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL)

The Real Work to Solve Metabolic Syndrome: Collaboration and Curiosity

Our collective obsession with finding the diet or lifestyle that resets the body is understandable. With metabolic health issues and obesity now so prevalent, many people are searching desperately for something that works. But the reality is this: genetics, hormones, microbiome diversity, past stress or trauma, and even the food supply chain likely all play roles too complex for any single plan to solve.

The reality is this: Solving metabolic syndrome will take more than diet books and before-and-after photos. It will take researchers, clinicians, community leaders, and—crucially—people living through it. Lived experience brings insights that data alone can’t.

Population Study

Some of the best data comes from studying populations in the world who have either avoided metabolic syndrome altogether or have seen an increase after some kind of collective lifestyle change.

One example is the Pima/Maycoba studies. Among the Pima people, who share the same ancestry but live in different environments, the contrast is striking. U.S. Pima in Arizona have some of the world’s highest rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes, while their relatives in rural Maycoba, Mexico—living more traditional, physically active lives with minimally processed diets showed far lower rates. PMC+2in.nau.edu+2

This is a textbook example of gene-environment interaction: the Pima had a high genetic predisposition, but the expression of disease varied dramatically depending on environment and lifestyle. Lifestyle factors (physical activity, diet, minimal processed food, manual labour) appear powerful enough to moderate or delay metabolic disease—even in high-risk groups. Environmental shifts (modernization, mechanization, processed food access, reduced physical activity) appear to trigger increases in obesity and diabetes, even in traditionally low-disease communities.

Social Media

Social media, for all its flaws, also offers an enormous opportunity for the kind of “meeting of the minds” that solving metabolic syndrome will take. Never before have we had such a window into the lived experiences of so many others. And people are posting about it. If you are at all interested in health and wellness and search on it, you know that there are gobs of people sharing their experiences with various dietary or fitness interventions and what worked for them—or didn’t. There is so much to learn from people’s honest stories on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, etc. But alongside that openness comes an overwhelming wave of wellness misinformation.

It can be really hard to be exposed to so much information all the time. Personally, I’m not interested in following advice that isn’t backed by solid, peer-reviewed research. Take diet trends that are commonly shared on social media for example—there’s no shortage of claims that eating a high-fat diet is good for you. But what does the research actually show? Certainly not that. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020–2025) recommend keeping saturated fat <10% of total calories, and the American Heart Association advises replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats to reduce cardiovascular risk. And while some people do see short-term results on very-low-carb/high-fat approaches (often from appetite suppression and early water/glycogen loss), systematic reviews find little to no long-term advantage over balanced diets for weight loss or cardiometabolic risk when calories are matched. A recent UK Biobank cohort study found that people eating a low-carbohydrate, high-fat (“keto-like”) pattern had higher LDL-C and apoB and about 2× higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events than matched participants eating a standard diet (adjusted analyses).

Beware of Gatekeepers

If a social media account claims to have the “real answer,” but asks you to pay to learn it—that is a no-go for me. True science evolves in public. The people who have been studying metabolic syndrome and the obesity epidemic for decades know there’s still a lot we don’t understand, and the ones truly invested in helping t solve it know there is more to learn. They share their knowledge freely—whether through peer-reviewed research or through personal stories that are transparent about methods, challenges, and results.

The Takeaway

Healing from metabolic syndrome and/or obesity is challenging in the current environment — there just isn’t a one-size fits all method or even consensus from the ‘experts’ on the right approach. In my view, those truly invested in finding widespread solutions should focus on building a culture of curiosity, collaboration, and transparency.

We might not be scientists or physicians, but here are some ways that I believe we all can participate in this fight for health:

Learn what it takes to keep your body metabolically healthy or to improve your current health. This includes understanding:

what a nutritious diet looks like

how much physical activity you should strive for

the importance of sleep

proper hydration

managing psychological and physiological stress

If you have found ways to improve your health, be willing to share your story openly and in full.

Support social media accounts that share their methods and results transparently.

Read or listen to ALL things online with a healthy dose of skepticism, and always come back to what the science supports.

The real solutions will come with our collective willingness to keep learning, together.

References

Grundy, S. M., Brewer, H. B., Jr., Cleeman, J. I., Smith, S. C., Jr., & Lenfant, C. (2004). Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation, 109(3), 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6

Alberti, K. G. M. M., Eckel, R. H., Grundy, S. M., Zimmet, P. Z., Cleeman, J. I., Donato, K. A., Fruchart, J.-C., James, W. P. T., Loria, C. M., & Smith, S. C., Jr. (2009). Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A Joint Interim Statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation, 120(16), 1640–1645. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644

Liang, X., Or, B., Tsoi, M. F., Cheung, C. L., & Cheung, B. M. Y. (2023). Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2011–2018: NHANES data analysis. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 99(1175), 985–992. https://doi.org/10.1093/postmj/qgad008

Kim, Y. J., Kim, S., Seo, J. H., & Cho, S. K. (2024). Prevalence and associations between metabolic syndrome components and hyperuricemia by race: Findings from US population, 2011 – 2020. Arthritis Care & Research (Hoboken), 76(8), 1195-1202. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.25338

Sacks, F. M., Lichtenstein, A. H., Wu, J. H. Y., Appel, L. J., Creager, M. A., Kris-Etherton, P. M., Miller, M., Rimm, E. B., Rudel, L. L., Robinson, J. G., Stone, N. J., & Van Horn, L. V. (2017). Dietary fats and cardiovascular disease: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 136(3), e1–e23. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510 American Heart Association Journals+1

U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ (see saturated fat <10% recommendation). Dietary Guidelines+2Dietary Guidelines+2

Naudé, C. E., Schoonees, A., Senekal, M., Young, T., Garner, P., & Volmink, J. (2022). Low-carbohydrate versus balanced-carbohydrate diets for reducing weight and cardiovascular risk. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD013334. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013334.pub2 (Conclusion: little to no difference in weight loss and CVD risk up to 1–2 years). Cochrane Library+2PubMed+2

Hall, K. D., & Guo, J. (2017). Body weight regulation and the effects of diet composition. Gastroenterology, 152(7), 1718–1727. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.056 (Mechanisms: appetite effects of ketosis; early weight loss from glycogen/water). Gastro Journal+1

Iatan, I., Raiker, R., Hussain, M., Bellissimo, M. P., Shahid, I., Ahmed, S. B., … Brunham, L. R. (2024). Association of a low-carbohydrate high-fat diet with plasma lipid levels and incident cardiovascular events in the UK Biobank. JACC: Advances. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.100924 JACC

Potassium Problems

Potassium and Metabolic Health: Why It Matters

In reviewing the research on nutrition and metabolism, I’ve found potassium to be one of the most interesting and important minerals. Adequate potassium levels are crucial for metabolic health — yet research shows that most U.S. adults aren’t getting enough. Some reports suggest that over 90% of adults fall short of the recommended intake.

The Adequate Intake (AI) for potassium, based on updated dietary reference intakes, is:

3,400 mg per day for men

2,600 mg per day for women

The FDA Daily Value (DV) — the target used on food labels — is 4,700 mg per day.

The Role of Potassium in Metabolism

Adequate potassium intake is essential for cellular and metabolic health. Here are a few key roles it plays in the body:

Cellular hydration: Potassium helps maintain proper fluid balance within cells, supporting optimal cellular function.

Glucose uptake: Sufficient potassium supports glucose transport into cells, which contributes to stable energy and metabolism.

Insulin sensitivity: Adequate potassium may improve insulin sensitivity and carbohydrate tolerance.

Pancreatic function: Potassium supports pancreatic beta cells, which play a key role in healthy insulin release.

Challenges with Potassium Status

Despite its importance, maintaining optimal potassium balance can be complex. A few challenges include:

Testing limitations: “Total body” potassium is difficult to measure. The potassium level on a standard metabolic panel reflects only a small fraction of total body stores.

Supplement safety: Potassium supplementation can be dangerous and should only be done under medical supervision. Too much potassium in the blood (hyperkalemia) can cause serious complications, including cardiac arrest.

Magnesium connection: Potassium and magnesium work closely together. Low magnesium can contribute to low potassium — yet magnesium intake is often inadequate and not required on food labels. It would be helpful if future labeling included magnesium for easier tracking.

Lifestyle factors: Stress, high sodium, caffeine, alcohol, added sugars, and processed foods can all contribute to potassium loss.

How to Support Healthy Potassium Levels

1. Track your current intake

Try logging your usual food choices for a few days using a tracking app that includes minerals, such as Cronometer. Compare your results to the Adequate Intake levels.

2. Include potassium-rich foods

Aim to incorporate a variety of naturally potassium-rich foods into your meals, such as spinach, potatoes (sweet and regular), beans, avocado, tomato products, coconut water, bananas, cantaloupe, oranges, apricots, dairy, salmon, tuna, almonds, pistachios, and pumpkin seeds.

3. Limit factors that cause loss

Support healthy potassium balance by getting enough magnesium, moderating sodium intake, and being mindful of caffeine, alcohol, stress, added sugar, and processed foods.

4. Explore balanced eating plans

Consider evidence-based patterns like the DASH Eating Plan, which was developed to promote overall nutrient balance — including potassium and magnesium. I personally find the DASH plan practical, sustainable, and adaptable.

Final Thoughts

Potassium plays a powerful and often overlooked role in energy metabolism, cellular function, and long-term wellness. Understanding where it fits in your daily nutrition can help you make more informed and sustainable choices.

Disclaimer

This information is provided for general wellness education only and is not a substitute for individualized nutrition or medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional or registered dietitian before making dietary changes or taking supplements.

References

Campbell, A. P. (2017). DASH eating plan: An eating pattern for diabetes management. Diabetes Spectrum, 30(2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.2337/ds16-0084

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d.). Your guide to lowering your blood pressure with DASH. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/WES09-DASH-Potassium.pdf

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. (2020). Potassium intakes of the U.S. population: What we eat in America, NHANES 2017–2018 (Data Brief No. 47). https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/DBrief/47_Potassium_intakes_of_US_population_1718.pdf

What is Health Coaching?

What Is a Health Coach?

A health coach is a trained professional who partners with and empowers clients on their path to greater wellness. Through evidence-based behavior change strategies, a health coach helps individuals build awareness, motivation, and sustainable habits that improve overall well-being.

The Role of a Health Coach

Health coaches are highly skilled in understanding the science of change and applying behavioral change theory. The primary goal of health coaching is to uncover and strengthen a client’s motivation toward their wellness goals, using a compassionate, non-judgmental partnership approach.

A health coach facilitates this process by recognizing that each client is the expert in their own life, holding both autonomy and responsibility for their choices. The coach’s role is to inspire belief in possibility and nurture self-efficacy—the inner confidence that says, “I can do this.”

Foundational Theories in Health Coaching

Health coaches draw upon well-established models such as Self-Determination Theory, which highlights the human needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness in cultivating internal motivation. Another key framework is the Transtheoretical Model of Change, which identifies where a person is in their change journey (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, or maintenance). Understanding this helps the coach tailor their approach effectively.

Motivational Interviewing in Coaching Practice

These theories come to life through the practice of Motivational Interviewing (MI)—grounded in Compassion, Acceptance, Partnership, and Empowerment. Using MI, a skilled coach helps clients resolve the tug-of-war between wanting to change and wanting to stay the same (ambivalence) by fostering “change talk” rather than “sustain talk.” The most effective coaches bring connection, presence, and balance to their sessions, embodying what’s known as the “spirit” of motivational interviewing.

The Health Coaching Approach

While health coaching is collaborative and goal-oriented, a coach does not diagnose, prescribe, or direct. Instead, with the client’s permission, they may provide education to support informed decision-making.

The outcome of a successful health coaching relationship is that the client discovers their own intrinsic motivation to make meaningful, lasting changes—often in areas like nutrition, physical activity, stress management, or lifestyle habits—leading to enhanced wellness and quality of life.

References

Lanier, C. H., Bean, P., & Arnold, S. C. (2024). Motivational interviewing in life and health coaching: A guide to effective practice. Guilford Press.

International Coaching Federation. (n.d.). What is coaching? https://coachingfederation.org/about/what-is-coaching

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

National Board for Health & Wellness Coaching. (n.d.). Scope of practice for health and wellness coaches. https://nbhwc.org/scope-of-practice

Let’s do Zone 2

Zone 2 Exercise and Metabolic Health

Zone 2 exercise has received growing attention for its potential benefits to metabolic health, and I’m a huge fan. Personally, it’s easier for me to commit to a Zone-2-ish brisk walk than a more vigorous workout like running. In Nature Wants Us to Be Fat, Dr. Richard J. Johnson (2022) recommends endurance-type exercise in Zone 2—about one hour, three or four times per week—to support mitochondrial health. The goal, as described in the book, is to keep exercise intensity around 70% of maximum heart rate, below the threshold where lactate begins to accumulate.

What Is Zone 2 Training?

Practically speaking, Zone 2 corresponds to roughly 60–70% of your maximum heart rate, often called a “conversational pace” (American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM], as cited in Elder, 2023; Cleveland Clinic, 2025). At this level, you should be able to maintain conversation but not sing.

There is some question, however, about whether this intensity is vigorous enough. Recent research indicates that while Zone 2 training is beneficial, it may not be uniquely optimal for mitochondrial or cardiorespiratory adaptations; higher-intensity intervals can sometimes yield greater benefits in less time (Storoschuk et al., 2025). Still, for many people, the accessibility and sustainability of Zone 2 activity make it a practical cornerstone of long-term metabolic health.

Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans

According to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2018), adults should engage in 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, or an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous exercise, to achieve substantial health benefits and lower the risk of chronic disease.

Moderate-intensity activity is defined as 3.0–5.9 METs on an absolute scale or about a 5–6 on a 0–10 perceived-exertion scale. In practical terms, this is an effort level where a person can talk but not sing.

HHS also created the Move Your Way campaign to help Americans apply these guidelines in daily life.

The “Active Couch Potato” Problem

Even when people meet weekly exercise recommendations, too much sitting can diminish the benefits. The term “active couch potato” describes individuals who exercise regularly yet spend most of their day sedentary (Owen et al., 2010; Dunstan et al., 2012).

Prolonged sitting—eight or more hours daily—has been linked to impaired glucose regulation and lipid metabolism, independent of structured exercise. I relate to this personally: during years of doing vigorous HIIT workouts, I’d often spend hours afterward sitting at my desk.

To counter these effects, research suggests adding short movement breaks throughout the day—standing, stretching, or walking for a couple of minutes every 30–60 minutes—to improve metabolic flexibility and reduce sedentary time.

Balancing Strength and Aerobic Training

The key takeaway: we need to move, and likely more than most of us do. Regular movement supports health and helps prevent metabolic dysfunction, but it’s not just about weight loss.

A growing social media narrative claims that strength training is more important than aerobic exercise. In truth, both are essential. Strength training builds muscle mass and metabolic resilience, while aerobic exercise supports cardiovascular and mitochondrial health.

The best approach is to create realistic, individual activity goals that can be maintained over time.

Measuring Activity: Understanding METs

If you’re looking for ways to assess or diversify your physical activity, the Compendium of Physical Activities from Arizona State University’s Healthy Lifestyles Research Center is a valuable tool. It lists hundreds of activities with their corresponding MET values—from sleeping (0.9 METs) to intense running (18 METs).

MET stands for Metabolic Equivalent of Task and represents the energy cost of physical activity relative to resting.

1 MET = energy expenditure while sitting quietly, roughly equal to consuming 3.5 mL of oxygen per kilogram per minute, or about 1 kcal/kg/hour.

Examples:

Light activity: < 3 METs (slow walking, light chores)

Moderate activity: 3–5.9 METs (brisk walking, gardening)

Vigorous activity: ≥ 6 METs (running, fast cycling)

The Compendium allows users to browse activities by type—household, recreational, or occupational—and compare MET values to national guidelines for a more informed fitness strategy.

Final Thoughts

Zone 2 exercise offers an accessible, sustainable way to support metabolic and mitochondrial health, especially when combined with other forms of movement and reduced sedentary time. Ultimately, consistency matters most: find the balance of aerobic and strength activities that fits your life, and keep moving regularly for long-term wellness.

Disclaimer

This content is for general educational purposes and should not replace individualized medical or exercise advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional before starting a new fitness or training program.

References

Johnson, R. J. (2022). Nature wants us to be fat: The surprising science behind why we gain weight and how we can prevent—and reverse—it. BenBella Books. (See exercise recommendation: sustained ≥1 hour, 3–4×/week.)

Storoschuk, K. L., Moran-MacDonald, A., Gibala, M. J., & Gurd, B. J. (2025). Much ado about Zone 2: A narrative review assessing the efficacy of Zone 2 training for improving mitochondrial capacity and cardiorespiratory fitness in the general population. Sports Medicine, 55(7), 1611–1624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-025-02261-y PubMed

Cleveland Clinic. (2025). Exercise heart rate zones explained (Zone 2 ≈ 60–70% HRmax). Cleveland Clinic

American College of Sports Medicine (via Elder, 2023). Moderate intensity ≈ 64–76% HRmax. Technologies, 11(3), 66.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd ed.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/paguidelines

Dunstan, D. W., Howard, B., Healy, G. N., & Owen, N. (2012). Too much sitting—a health hazard. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 97(3), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.020

Owen, N., Healy, G. N., Matthews, C. E., & Dunstan, D. W. (2010). Too much sitting: The population-health science of sedentary behavior. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 38(3), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Move Your Way. https://health.gov/MoveYourWay/

Ainsworth, B. E., Herrmann, S. D., Jacobs Jr., D. R., Whitt-Glover, M. C., Tudor-Locke, C., & Barreira, T. V. (2024). The Compendium of Physical Activities (Adult, Older Adult & Wheelchair versions). Arizona State University Healthy Lifestyles Research Center. https://pacompendium.com/

Ainsworth, B. E., Haskell, W. L., Herrmann, S. D., Meckes, N., Bassett, D. R., Tudor-Locke, C., ... & Leon, A. S. (2011). 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(8), 1575–1581. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12

.

OWN Your Health Foundation

OWN your health foundation

If you are looking to improve your metabolic health, make sure you OWN the basics first. It is so easy to go down the social media rabbit You may ultimately find your answer right here 🎯 in the 3 most important things we all know we need for good health.

Oxygen 🌱 Water 💧 Nutrition 🥗

We all know these are essential for life—but are you sure your foundation is solid?

A large portion of U.S. adults are chronically dehydrated, and many people unknowingly fall short on key nutrients in their diet. Add to that the body’s ability to deliver and use oxygen efficiently—a cornerstone of metabolic health.

There’s a mountain 📚 of research linking hydration, nutrition, and oxygen utilization (through physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness) to better metabolic outcomes.

Lately, conversations about hormones—especially cortisol—are everywhere on social media. If you’re concerned about cortisol, it’s worth looking at the basics first: problems with hydration, nutrition, or oxygen use can all raise cortisol levels.

Sometimes the right answer really is the simple one! 💪

Credit: 📖 Inspired by the principle of Occam’s Razor and the wisdom of Albert Einstein:

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.”

Leptin and Weight Management

Leptin

Ever Heard of Leptin?

Ever heard of leptin? It’s a hormone that plays a critical role in regulating your appetite, energy levels, and body weight. 🌟

Leptin is often referred to as the satiety hormone because it signals your brain when you’ve had enough food, helping you feel full after eating. However, when leptin levels are out of balance, they can contribute to increased hunger, overeating, and weight gain. 🤯

Leptin’s Role in Metabolism

Leptin is produced by fat cells and communicates with the brain — particularly the hypothalamus — to regulate appetite and energy expenditure.

High leptin levels signal that you have sufficient fat stores, which should reduce appetite.

Low leptin levels can trigger hunger and lead to overeating or weight gain.

Basically, leptin is the hormone that should be saving us from excessive energy intake — from overeating. When it’s working properly, leptin helps regulate appetite, energy use, and body weight. In many ways, it may be the key to a properly functioning weight management system.

Why Weight Management Shouldn’t Be So Hard

It’s common sense to think that maintaining a healthy weight shouldn’t be so difficult. We weren’t meant to count calories or track every macro. No other animal in nature does that to stay at its ideal weight. Sure, some animals have metabolic challenges, but most maintain a consistent, stable body composition naturally.

Humans, on the other hand, put enormous effort into measuring, restricting, and managing — yet we remain the species most prone to weight fluctuations and metabolic struggles. So what gives?

Leptin Resistance: When the Body Stops “Listening”

Since leptin is the hormone that helps prevent overeating, a natural first question might be: “Why don’t I produce enough leptin?”

But for most people, that’s not the issue. In many cases, despite having plenty of fat stores, the body becomes resistant to leptin’s signals — a condition known as leptin resistance. This can lead to chronic hunger, overeating, and difficulty losing weight. The real problem is that the brain and cells stop responding to leptin. The signal that should say “you’ve had enough” no longer gets through.

Leptin resistance is often linked to metabolic conditions such as obesity, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation.

Leptin Resistance and Metabolic Health

Leptin resistance can create a feedback loop that makes managing appetite and energy balance even harder. The body interprets the lack of signal as starvation, increasing hunger and slowing metabolism. Over time, this pattern can contribute to weight gain, fatigue, and metabolic dysfunction — even when calorie intake isn’t excessive.

How to Improve Leptin Sensitivity

Eat a balanced diet: Focus on whole foods, healthy fats, lean proteins, and fiber to support healthy leptin function.

Move regularly: Physical activity improves leptin sensitivity and overall metabolic health.

Manage stress: Chronic stress disrupts hormonal balance and can impair leptin signaling.

Prioritize sleep: Poor sleep alters leptin and ghrelin levels, increasing hunger and cravings.

Restoring Balance

This is one example of why Rebase Wellness aims to take a systems-based approach to well-being — recognizing that hormones like leptin are part of a larger network influencing energy, metabolism, and mindset. Weight gain or difficulty losing weight is not a moral failure or a lack of willpower. It’s a signal that something in the system is out of balance. Sustainable change rarely comes from a single strategy, like calorie restriction; it requires understanding and addressing the interconnected factors that support metabolic health and long-term wellness.

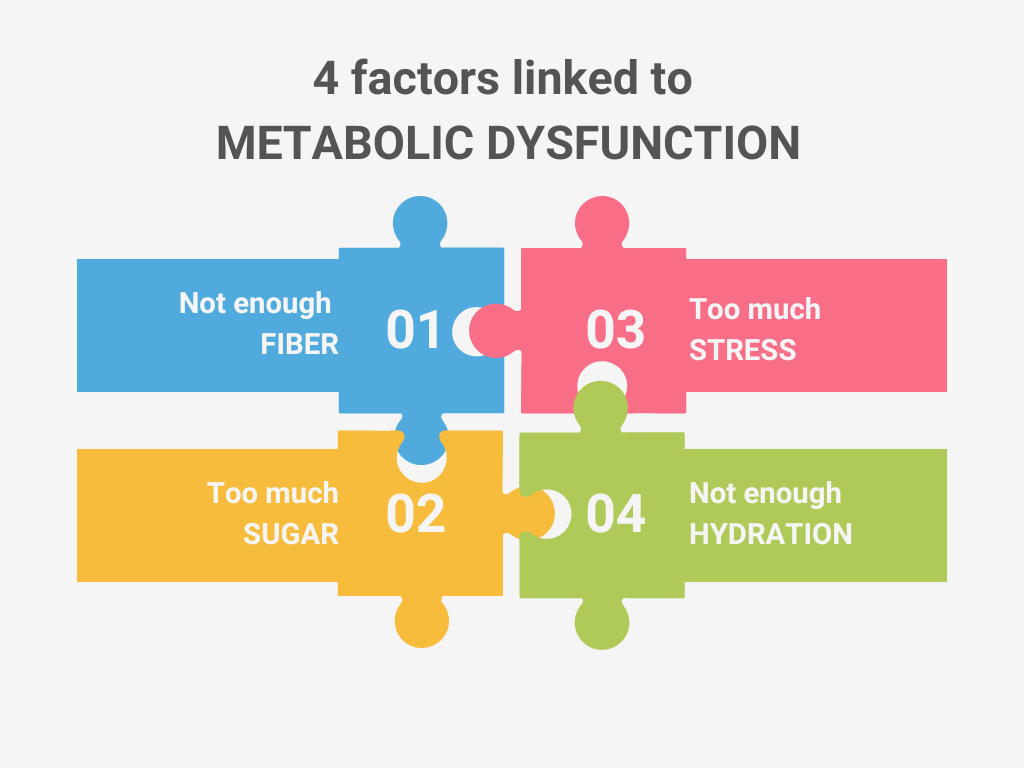

Four Factors linked to Metabolic Dysfunction

4 factors linked to metabolic dysfunction

When searching for information on improving metabolic function, the solutions are elusive at best and impossible at worst. The information shared online and through social media is often too generic to be helpful—such as “Eat less, move more”—too specific—like “Eat almonds to reduce belly fat”—or even contradictory and potentially damaging. Even books authored by doctors and scientists offer conflicting advice on what actions to take.

It is encouraging that there is a substantial level of attention on the topic of metabolic issues, and scientific and medical research are clearly progressing. However, there does not yet seem to be a clear-cut answer as to why millions of U.S. adults and children are dealing with metabolic syndrome. Hopefully, in time, the causes will become much more clear.

In the meantime, there are common themes in published scientific and medical research that may offer helpful insights. In my reading and research, four factors are most frequently associated with metabolic dysfunction:

1. Not Enough Fiber

Getting enough fiber is associated with reduced metabolic disease risk factors (Quagliani & Felt-Gunderson, 2016). According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020), over 90% of adults do not meet the recommended daily intake of fiber. Nutritional goals vary from 25 to 31 grams a day for adults.

Processed carbohydrates—like crackers and chips—are often stripped of their natural fiber content. Choosing more whole foods, fruits, vegetables, and legumes can help close that gap.

2. Too Much Added Sugar

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 also report that a majority of Americans exceed the recommended limits for added sugar (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020).

We all recognize when we’re indulging in obvious sources of sugar, like cupcakes or donuts. However, added sugars also hide in many foods—such as salad dressing, bread, juice, or pasta sauce. Common types of added sugars are listed on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website.

Fortunately, food labels now make it easier to identify added sugar. Since 2021, manufacturers have been required to include “Added Sugars” on nutrition labels (Magnuson & Chan, 2019). For example, GoGo SqueeZ applesauce lists 13 g total sugars and 0 g added sugars—indicating that no sugar was added during processing.

3. Too Much Stress

Stress has been linked to obesity and metabolic dysfunction (Tomiyama, 2019). The stress may be physiological, psychological, or physical. For anyone struggling with metabolic issues, it’s worth identifying sources of stress that can be reduced or eliminated. Some stressors are obvious, while others may be subtle and chronic.

4. Not Enough Hydration

We’ve all heard the advice to “drink more water,” and research supports it. Inadequate hydration has been associated with higher body mass index (BMI) and obesity (Chang et al., 2016).

The amount of water an individual needs depends on factors such as climate, activity level, and body size. The Mayo Clinic recommends approximately 2.7 liters daily for women and 3.7 liters for men.

References

Chang, T., Ravi, N., Plegue, M. A., Sonneville, K. R., & Davis, M. M. (2016). Inadequate hydration, BMI, and obesity among US adults: NHANES 2009–2012. Annals of Family Medicine, 14(4), 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1951

Magnuson, E. A., & Chan, P. S. (2019). Added sugar labeling. Circulation, 139(23), 2625–2627. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040325

Quagliani, D., & Felt-Gunderson, P. (2016). Closing America’s fiber intake gap: Communication strategies from a food and fiber summit. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 11(1), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827615588079

Tomiyama, A. J. (2019). Stress and obesity. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102936

U.S. Department of Agriculture, & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2022, October 12). Water: How much should you drink every day? Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/water/art-20044256

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, January 5). Get the facts: Added sugars. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/php/data-research/added-sugars.html

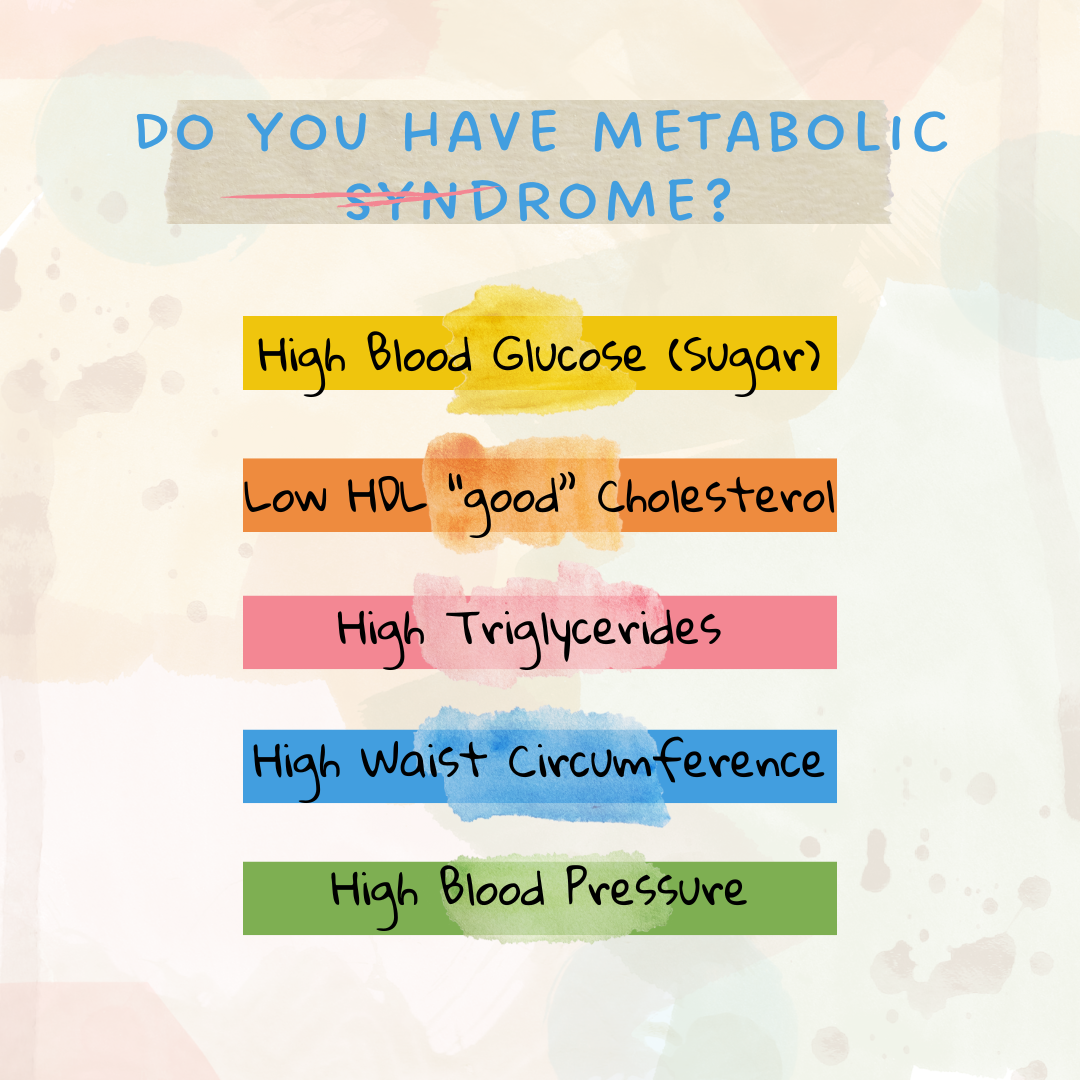

Metabolic Syndrome - America’s Public Health Crisis

What Is Metabolic Syndrome and Why It Matters

Do you have metabolic syndrome? Even if you’ve never heard the term, it’s possible that you may be experiencing it — in fact, there’s a significant chance. According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2022), “metabolic syndrome is common in the United States. About 1 in 3 adults have metabolic syndrome.”

Unfortunately, in addition to one in three adults, a growing number of children are also affected by this health-impacting condition.

Defining Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome has been recognized for decades, though its definition has evolved. In 2009, several major health organizations — including the American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute — collaborated to create a unified definition of metabolic syndrome (MetS). This remains the clinical standard used today (Alberti et al., 2009).

According to these guidelines, metabolic syndrome can be diagnosed when an individual has three or more of the following conditions (Alberti et al., 2009):

High blood glucose (blood sugar)

Low HDL (“good”) cholesterol

High triglyceride levels

Large waist circumference

High blood pressure

Why Metabolic Syndrome Is a Public Health Concern

Metabolic syndrome is a serious health issue in both adults and children. Its importance lies not only in its direct impact but also in its strong connection to other chronic diseases — particularly heart disease and type 2 diabetes (Alberti et al., 2009).

Given its growing prevalence, metabolic syndrome is now considered a major public health concern. To reverse this trend, we would need to see clear evidence that rates are declining across the population. Despite ongoing research, awareness campaigns, and preventive health efforts, a large-scale solution remains elusive. Still, continued education, early detection, and lifestyle support are critical for improving outcomes.

References

Alberti, K. G. M. M., Eckel, R. H., Grundy, S. M., Zimmet, P. Z., Cleeman, J. I., Donato, K. A., Fruchart, J.-C., James, W. P. T., Loria, C. M., & Smith, S. C., Jr. (2009). Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation, 120(16), 1640–1645. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, May 18). What is metabolic syndrome? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/metabolic-syndrome

Fruits and Veggies First!

Fruits & Veggies First

I’ll be honest – I didn’t grow up eating a lot of whole fruits and vegetables. It just wasn’t something I was accustomed to. I have wondered if this is one reason that I have struggled with metabolic issues as an adult. In my health journey, have I had to teach myself how to incorporate them into my life. 🍏

When my kids were little, I knew I wanted them to eat more whole fruits and vegetables that I did so I would ask them eat the fruit and/or vegetables that were on their plate first. It worked (mostly) and as teens they now eat them regularly and enjoy a good variety. They are way more likely to grab a banana or apple as a snack than I am.

When I started to try to really up my fruit and vegetable intake, I realized that the same ‘trick’ might work for me. The goal is to start every meal (or snack) with a fruit, veggie or a salad 🥝🍓🥒 no matter what the meal. I try to just keep it simple - today before lunch I simply peeled, cut and ate a huge carrot.

Here’s how it can work:

👉 Before eating your usual meal, eat some fresh, colorful produce of some sort

👉 It fills you up with nutrients and fiber, before reaching for the less healthy options

👉 What is really cool is that over time, your body gets used to the idea of eating fruits and veggies first and you’ll start craving them more! 🌟

Fruits and vegetables are packed with essential vitamins and minerals like:

Magnesium 🥑 (for relaxation and nerve function)

Potassium 🍌 (for heart and muscle function)

Vitamin C 🍊 (for immune support and skin health)

Vitamin A 🥕 (for healthy vision and skin)

Vitamin K 🥬 (for blood clotting and bone health)

These nutrients are key to helping your body and cells function best. Many studies have linked various vitamin and mineral deficiencies to metabolic issues such as insulin resistance and blood sugar issues.

Again, keeping it super simple is the key to success. Whether it’s an apple before lunch or a side salad before dinner it’s all about creating the habit and getting the nutrients. 💚